HOW DID SOMEONE WITH NO BACKGROUND IN ARCHITECTURE OR ART HISTORY WIND UP DOING THIS PARTICULAR PROJECT?

|

So, why me? How did a guy who spent most of his life in New York City working as a film and video editor and playing drums in a never ending stream of punk, hardcore and garage bands wind up being the one who photographed an architectural aspect of New York City’s public landscape for so many years? I wouldn’t have seemed a likely candidate, with no background or studied interest in architecture or sculpture. Truthfully, I know more about movies than I do any other art form. I can bore relatives, friends and well meaning conversationalists with a wealth of details about my favorite auteurs and individual films, about film theory and production, but ask me to discuss aspects of architectural history and you’ll find my knowledge is decidedly pedestrian, at best.

It wasn’t until I interviewed G Augustine Lynas in 2013, in the context of an conversation about artists and what motivated them, that I seriously thought about what hook had grabbed me originally and kept me tied to my project for all these years. He asked me why, what was it that had drawn me to my chosen subjects so strongly? I found myself thinking about it deeper than I had before, beyond the different stages of interest that had held me as I encountered more and more stone faces and learned more about them over the years. I suddenly remembered something I hadn’t thought of in at least 30 years, that as a very young child I had carved faces into the soft clay lining the bluffs on a beach my family had vacationed near. But then, as quickly as that image appeared to me, I realized it was actually a different early experience of childhood that had been integral to my interest - my sympathy for the monsters in old horror films. As a young child, exposed to monster movies via television, I first developed what would become a life long empathy for outcasts and so called freaks, for the misunderstood and those who didn’t fit in. Later in life I would go through periods where I could identify personally with some of those terms and apply them to myself psychologically, but as a child it was directed purely outward, beyond the simple awkwardness of being so young. I remember vividly that I viewed creatures as different as “Frankenstein’s Monster,” “King Kong,” “The Wolfman” and even the giant mutant ants of “Them!” with sympathy, feeling that they hadn’t asked for nor deserved their fate. In addition to simply thinking they were cool, I felt empathy for them. When I first spotted a stone face in my neighborhood in the late 80’s, having recently moved to New York City from the suburb of Syosset, it happened to be a particularly decrepit one, a face that had grown over time to have an almost monstrous quality. The tragedy of its deformity, combined with my subsequent realization that many people never even noticed it was there, triggered an empathetic reaction. In a way, I came to view that sculpted face as a forgotten outsider, made “monstrous” by the unkind treatment it had received through neglect and the passage of time in the harsh city environment. As the years passed and I saw more and more of these sculptures they became less and less monstrous to my eye, but no less fascinating. One fact remained unchanged, I found the sculptures with the most wear, the faces with the most visible damage, to be the most compelling subjects. One of my favorite quotes comes from an episode of “Monty Python’s Flying Circus.” John Cleese and Graham Chapman are in their famous Pepperpot costumes (in drag, playing shrill and decidedly un-glamorous housewives) and are visiting an art gallery while their children run amok offscreen, destroying various priceless paintings and receiving exaggerated, admonishing slaps in return, heard as comedic punctuation. As the Pythons carry on in conversation and eventually begin to eat the paintings in the gallery, Cleese ends the sketch with the line “I may not know much about art but I know what I like.” The spark that began my project and led to my making a short video on the subject in 1997 was as simple as that. I simply liked the faces I had found, and was continually surprised that so many unique ones were there. I knew it was something I wanted to explore. The mystery of it excited me, and so did the adventure of setting out to discover them for myself throughout the city I lived in.

|

Perhaps because I absorbed that line from Python at a young age, and associated it with something I love, meaning the Python’s sense of humor, I never looked at the sentiment as being negative, even if it was intended as such. It wasn’t until later in life that I learned that variations of that phrase had been uttered before, and that many in the art world definitely didn’t view it as positively as I did. They considered it something of a cliche, associated with the uncultured tastes of the “unwashed masses” and a lack of intellectual curiosity. For whatever reason, I’ve never thought of it that way at all. It described how I felt when I first saw the artwork of Francis Bacon, Salvador Dali, H. R. Giger and Hieronymus Bosch. I associated it with the feeling of instinctively liking something. It could be an appreciation for something that you recognize as personally appealing, even if you don’t fully understand why, what went in to its creation, or the history of the specific discipline that preceded it. A work of art of any kind can appeal to a person for a myriad of reasons, even if they find that other forms of that art normally don’t “speak” to them.

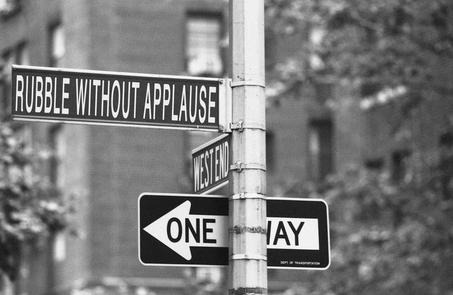

I often thought of that Python quote over the years as I photographed on the streets of New York City. I met hundreds of people in that time, passersby who were interested enough in what I was photographing to ask me about it, and then stop for a chat. One thing that became clear to me is that interest in these stone faces seemed to cross most all boundaries once I explained what I was doing and shared some of the photographs. It wasn’t limited to people you’d think of as academics or those you might peg as having a pronounced artistic nature. I met people of all ages, ethnicities, and appearances who seemingly held little in common other than they either lived nearby or happened to be walking down the street when I was photographing. Tourists, local residents, bikers, rappers, punk rockers, babysitters, housewives, janitors, restaurant workers, bike messengers, postal workers, movers, delivery men, utility workers, senior citizens and children - the interest in these stone faces seemed to have near universal appeal once they were pointed out and presented. Most often, it was the simple beauty of these sculptures and the emotions one could read on their faces that people reacted to. There was also an accompanying appreciation for the fact that someone had made this effort to add interest to the cityscape so many years ago. Just as this subject had captured my interest, I knew it could hold interest for others. These faces can do a lot of talking all on their own to those who observe them, and that dialogue isn’t limited to those with an understanding of their place in architecture or art history. People often wanted to know more and asked what I had learned about them, and why they were there, and I’d happily tell them all I knew. This is what led to the interviews I conducted for my book. It became my intention to find a way to make it more of a personal work, of learning in progress, as opposed to a dry or comprehensive academic overview. I wanted to make a book that reflected my own experience of learning about these sculptures over several years, and presented it in the manner of the informal conversations I had shared with so many strangers on the streets of the city. So hopefully, if you are reading about this "rubble without applause" for the first time and aren’t normally drawn to this kind of subject... You may not know much about art, but you know what you like. |

Video, Photographs and Content by Alan Bazin © 2021